The eighteenth-century travel diary of a captain’s son

Between 1783 and 1786, the captain’s son Nicolaas Abraham van Rijneveld (1766-1849) was on board the Noordholland (North Holland), the ship of the line commanded by his father, Captain Daniël Jan van Rijneveld (1742-1795). In the first part of this blog, I introduced Nicolaas’s published travel diary, Reize naar de Middelandsche Zee (Journey to the Mediterranean Sea) (1803), and in the second part I described the route of the Noordholland. Central to this part is Nicolaas’s trip to Pisa.

On Saturday 11 December 1784, Nicolaas travelled from Livorno to Pisa ‘in the company of three other Gentlemen’. (Van Rijneveld 1803: 84) They left in a carriage drawn by four horses. According to Nicolaas it was a pleasant ride: the path was paved and there were many fruit trees, and the company had a view of fields, farmlands, vineyards and ‘farmer houses’. After more than an hour’s ride they paused at a ‘farmer’s inn’ in the middle of a forest, where the horses could drink water and the gentlemen spotted a monastery. (85) After this short stop they got back into the carriage; two hours later they reached Pisa.

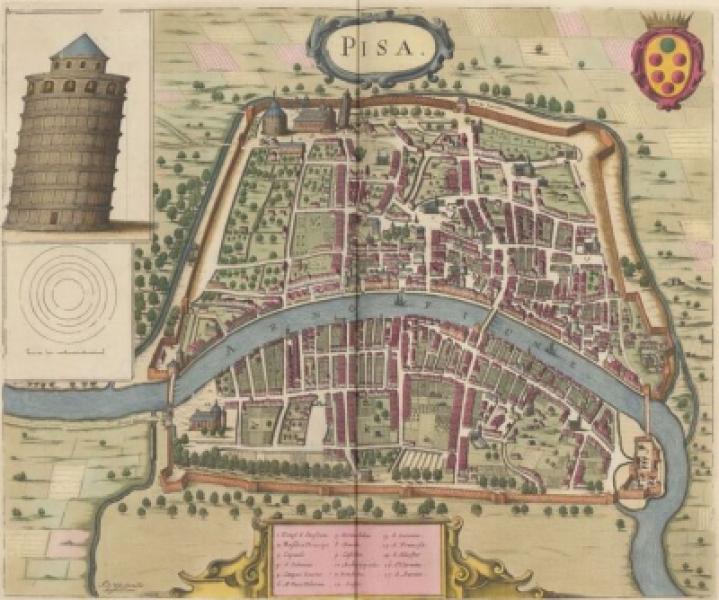

Nicolaas enjoyed the city. The streets were wide, straight and airy – ‘in the Italian taste’. The city was surrounded by high walls with gates in the style of classical antiquity. Because of the beautiful classical buildings in the city, Nicolaas labelled Pisa ‘renowned and noteworthy’. He notes that there were few people in the city and then elaborates on its history. For example, he describes a bridge on which the annual ‘Bridge Game’ was held. This was ‘a remnant of the pagan fencing games or Roman camp battles’. The Bridge Game was abolished by the Duke shortly before Nicolaas’s visit to Pisa, because of the dangers involved. (85-87)

The company stayed in ‘the Husaar, one of the most important lodgings, where [they] also found good service and table’. (88) After their lunch there they visited a Tuscan nobleman, Count Catanti, who not only married a Dutchwoman but had also visited the country himself. The company was indeed pleasantly surprised when they entered his house – it was furnished in the Dutch manner, according to Nicolaas.

The next day, they were given a carriage by the Count to travel in the morning to the bathhouses in a village just outside Pisa. The wooden bathhouses were built next to the Grand Duke’s palace. The right wing contained the Grand Duke’s marble bath, a bath for ladies and several small single baths. The left wing housed a large general bathroom and a few small rooms. According to Nicolaas, the bathers were provided with everything, such as a bed and a fire basket. Each bath had three taps, for hot water, and hoses so that you could spray the water in a certain direction. ‘The warm mineral bath water is more than lukewarm, has a slightly sweetish taste, reminiscent of milk, and when drunk in sufficient quantity, is laxative and blood purifying’, according to Nicolaas. (90)

Unfortunately, the party did not have time to visit the Grand Duke’s palace and, immediately after bathing, they boarded the carriage again for Pisa. They were dropped off at the Cathedral and returned the carriage to the Count with many words of thanks. Nicolaas was very impressed by the church: ‘This main church or cathedral is an unusually proud building, worthy only of a journey to Pisa.’ (90) It was a cruciform church with three entrances. The doors were cast in metal and had Biblical scenes on the panels. The captain’s son admired the craftsmanship. The inside of the church did not detract from the outside: there were ninety pillars of different kinds of marble, there were paintings by famous masters, the altar was made of beautiful marble and enriched with mosaics.

By the way, the weather was not favourable: it was cloudy and rainy. After describing the Tower of Pisa – another masterpiece according to Nicolaas – and an ancient temple, the gentlemen visited the Campo Santo cemetery. ‘Here one also sees a crowd of old marble coffins, provided with statuary and praise or with ancient inscriptions, which are dug out of the ground from time to time; they probably contain the coffins of the ancient Etruscans or of the Romans.’ (93) In the cemetery they learned something peculiar:

the earth in this Campo Sancto [has] the characteristic that the corpses buried here swell very much the first day, are completely crushed and dehydrated the second day, and lie in their skeleton the third day, consumed to dust. This strange transformation of the corpses in three days has been shown to us on the wall painted in Fresco as a remarkable event. (93-94)

After Campo Santo they passed the observatory, ‘a modern building’. (94) And then they walked past the ‘Foundling house’. In one of the walls of this house was a window with a semi-circular cage on a spindle. The cage was open on one side ‘so that one can deliver the living consequences of a secret love trade, in this house for nurture, unnoticed’. (94) An unwanted child could thus be placed in the cage. Then a shrill bell was rung to alert the people in the Foundling house so that they could take the ‘little child from the cage into the house’. (94) When the shrill was pulled, it was forbidden for the people in the house to open the door or go outside to identify the person. In this way, their anonymity was guaranteed.

A little later the gentlemen walked past the church and the palace of the Knights of St. Stephen, and then passed the bourse, which by the way no longer had any function (commerce had already died out in Pisa) – ‘it serves only as a memorial to the once flourishing state of commerce in Pisa’. (95) Before returning to the ship they also wanted to visit the Hortus Medicus and the Cabinet of Natural Rarities, ‘but these two [they] could not see, due to the rudeness of the attendants’. (95) A visit to the theatre was also out of the question – no one was there. They therefore spent their last hours in a coffee house. ‘From there [they] returned to [their] lodgings, and shortly afterwards set out for Livorno, well satisfied with all [they] had been able to do in the short time of [their] leave, to satisfy [their] appetite, without complaining of the expenses made.’ (96)

Bibliography

Van Rijneveld, N.A., Reize naar de Middelandsche Zee, Amsterdam 1803.