The Baccalare women

Many of the travel reports in the blogs on this website tell the stories of Dutch people in Italy. The nice thing about De vrouwen Baccalare (The Baccalare women) is that this book turns that situation around: instead of the experiences of Dutch people in Italy, here we read about the experiences of Giuseppina Bianchi, a young Italian woman from Florence who leaves for the Netherlands. Although Giuseppina was only supposed to work for a family in Amsterdam for a limited period of time, she stays behind in the Netherlands due to an accumulation of events, only to have to build a life there. Van Hoogstraten-Schoch compares the story of Giuseppina’s life with that of a fairy tale and opens the story as follows:

When we were little and listened anxiously to fairy tales, we heard of princesses being changed into animals by a sorcerer. We did not like this at all, and we were not satisfied until the story had reached its climax, and the poor enchanted person had been freed from her predicament and turned from a nightingale back into a princess. […] I wonder if the story of Giuseppina Bianchi’s life was anything other than a fairy tale of a princess who underwent a metamorphosis; only that the fairy tale ended very differently from all the others. The only thing it has in common with most of them is that we can also end the story with the one sentence that we loved so much in our childhoods: ‘and they lived happily ever after.’ (Van Hoogstraten-Schoch 1935: 5-6)

The comparison of Giuseppina as a fairy-tale princess in the story of her life, perfectly represents the feeling that comes over you as a reader of her experience in the Netherlands. The story makes it clear that Giuseppina feels particularly alienated, alone and trapped in the Netherlands. Like a fairy-tale princess locked in a tower, Giuseppina seems, throughout her 26 years in the Netherlands, to long for liberation – for a return to sunny Italy. She is heartbreakingly homesick and cannot share this with anyone. Although her husband Jacob loves her dearly, he is no support for Giuseppina. As a down-to-earth Zeeuw (person from the Dutch province Zeeland), he only knows the advice of his mother when it comes to matters of the heart, who always sternly said: ‘do not stir in it.’ Afraid of upsetting his wife even more, he does not ask about her feelings.

The two live in a dark backroom of the hotel where Jacob works, they have three children and because of her role as housewife Giuseppina hardly goes outside. She understands nothing of Dutch culture: the always calm and quiet people, the lifeless streets and especially the fear of sentimentality. She also feels no connection with her two eldest children, who are as Dutch as it gets and understand nothing of their ‘strange’ Italian mother. Giuseppina spends her days in seclusion, daydreaming about beautiful Italy, knowing that her husband would understand nothing of it:

Imagine! she thought, startled, if the brakes that work in every human being stopped working, just as they do in cars; if, one day, she found herself on a train without Jacopo. It would not even be pleasant to go with him; you cannot visit Italy with Holland in your pocket, you have to experience it. At the most beautiful places, he would patiently and ever so kindly say, ‘Are we staying here? Are we not moving on? Is there something to see here? Do we look at the water all day? Or at that mountain or at the stars? Is there anything special about this church? Don’t you think the people here are midgets? I put them all in my pocket…!’ (39)

The birth of their third child means a twist in the story’s plot, for unlike the older children, this one looks more Italian than Dutch. They call her Giulia. Giuseppina teaches Giulia Italian songs and tells her endless stories about her homeland. Giulia, like her mother, has a great talent for painting and, despite the protests of her father, brother and sister, she starts art school.

One day, Giulia wins a drawing competition: she is allowed to study in Florence for three months. Giuseppina is exhilarated. She prepares Giulia for her departure and looks forward to seeing, through her daughter’s eyes, a glimpse of the country she so longs for. When, a few weeks later, Giulia writes that she has broken her leg in an accident, she is determined to leave for Italy to assist her daughter. Despite Jacob’s disapproval, she leaves for Florence, seizing the opportunity to see her beloved country one more time.

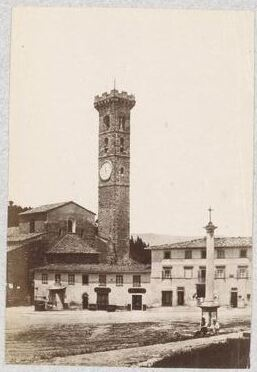

Just as after the metamorphosis in a fairy tale, Giuseppina is overjoyed in Italy: she enjoys all the splendour of Florence, visits museums and picks up her old love of painting. Mother and daughter stay with Giuseppina’s sister – also called Giulia – with whom Giuseppina had previously lost contact. Although she had initially planned to go to Italy for a few weeks, she ends up staying away for months. She hears nothing from Jacob in the meantime. One day she leaves for the town of Fiesole to paint on the hilltop opposite the church of Santa Maria. Suddenly she feels someone behind her and turns around – it turns out to be Jacob.

Jacob came to Florence to ask Giuseppina to come back home. However, this does not happen before she has been able to show him a piece of Italy. The loss of his wife has changed Jacob: he promises that from now on he will always ask her what is on his mind; he never wants to lose his wife again. Jacob promises her that they will save up, so that they can return to Italy together every once in a while. At home, he even surprises her with a studio that he has made for her so that she can continue to paint. After spending a few more beautiful days together in love, they return to the Netherlands. Giuseppina’s story ends here, and although this does not happen with the beloved ‘and they live happily ever after’, the ending does remind one of this:

She never saw Italy again, but she didn’t need to: Italy was in her heart, Italy was in her memory, and together they had souvenirs, Jacopo and she. Over the hilltop in Fiesole, just opposite the church of Santa Maria, […] there Giuseppina Bianchi had again chosen Holland for ever as her country; there she had once again put her hand, as meaningfully as on her wedding day, in Jacopo Baccalare’s; there she had understood what he meant to her, and with a happy heart she had followed him to the country, which from now on would be hers better than ever. (88)

Bibliography

Hoogstraten-Schoch, Amanda Augusta van, De vrouwen Baccalare, Amsterdam 1935.